ABSTRACT

This is a historical study of the rise and fall of the citrus industry in Apopka, Florida. The citrus industry was paramount in Apopka during the late 1800's - accounting for most of the city's economy, employment, the establishment of new businesses, development, steady income source for residents, and more. However, the citrus industry fell victim to several devastating ice freezes over the span of a century, which eventually led to its downfall. In this paper, the argument is made for a hypothesis, contending Apopka's citrus industry's fall was directly related to the freezes' magnitude and frequency. The argument is made that the initial influx of people to the Apopka area came due to the Armed Occupation Act of 1842, out of the need to inhabit and protect the Peninsula of East Florida from the native Americans and other threats. The research identifies the cultivation of land in Apopka to harvest citrus fruits to be a once lucrative practice that; (1) served as a gateway for some early settlers and (2) rendered high profits and financial gains for others in the area. Analyzing the original historical data and artifacts on the city of Apopka indicates that early settlers relied heavily on the production of citrus fruits. The research also reveals a strong reliance on the citrus industry and proves the impact freezes of 1894 and 1894 are strongly related to the citrus industry's current state.

Keywords: impact freezes, liquid gold rush, Apopkans, Apopka’s citrus industry, Florida freezes, Agricultural, Historical

THE METHODOLOGY

The Rise and Fall of the Citrus Industry in Apopka, Florida: A Historical Perspective began as a course assignment at the University of West Florida. We were to conduct and write a historical research study on a related topic of our interest. However, I was utterly infatuated with the history of the City of Apopka, plus the treasure hunt aspect to archival and historical research, I have taken the research well beyond the scope of the course and the requirement of the assignment. In completing this study, the methodology used included a review of historical artifacts housed at the Apopka Historical Society and Museum. This researcher utilized excerpts of Acts, treaties, and images from the Archives of the United States Congress. Data and images were collected by visiting historical sites. Content analysis was performed on archival data derived from local, regional, state, and national databases.

INTRODUCTION

Citrus groves, cultivation, harvesting, juice processing, packing houses, and shipping to northern markets were all part of the natural mechanism that dominated the lives of early settlers in the Apopka area in the 1880’s, and a significant part of the 1900s. The citrus industry is what fueled the economy for almost a century. In this, the introduction to the allure of the city’s rich local history and culture. Nothing appears to be more insightful than the infamous impact freezes that devastated the citrus industry in Florida. It is precisely these historical events that beckons further inquiry, investigation, and research.

Figure 1 Map of Apopka (1887)

Taken on February 7, 2017, this photograph shows an 1887 map of Apopka - displayed at the Apopka Historical Society and Museum of Apopkans.

Figure 2 Taken in the 1800s, this photograph shows the remains of an orange grove in Florida after the 1894 and 1895 freezes.

Figure 3 Taken in 1894, this photograph shows the freeze damage that many groves in Florida experienced after one of two freezes (1894, 1895).

Apopka, a once symbolic ambassador of Florida's citrus industry, has dwindled to nihility. The sheer enormity of the groves' destruction, closure of businesses, unemployment, and the economic impact is modestly disheartening. Citrus was paramount in the late 1800s; the major Florida freezes of 1894 and 1895 profoundly changed the citrus industry's direction in Florida (Attaway, 1997). This event bookmarked an early stage of what became a century-long assault reminiscent of a well-calculated and enduring military campaign designed to slowly and permanently incapacitate or annihilate the enemy. This type of military strategy has a likeness to what transpired with Apopka's citrus industry, except it was an assault perpetrated by nature on the orange groves. An attack that culminated with a decade of relentless impact freezes (1981, 1983, 1985, and 1989) that ultimately devastated the industry in a way so unprecedented that it is now virtually nonexistent. By the end of the 1989 winter, the Apopka growers had endured decades of harsh ice freezes, leaving behind groves of damaged crops caused by ice formation on citrus trees (Attaway, 1997, 14). The entire citrus industry of Apopka suffered years of compounding assault and losses that made recovering an almost impossible task (Jackson, 1988).

In the following paragraphs, I expound upon that which is alluded to above, namely, the story of the rise, the apex, and fall of the citrus industry in Apopka, Florida. Special attention is paid to a hundred-year period of freezes in Apopka's history, between 1882 to 1989, challenging industry participants and influencing the citrus industry's overall direction.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF APOPKA

Without first having insight into the history of Apopka, no thoughtful examination of the city’s citrus industry will be complete. Apopka, or as the Native Americans pronounced it “Ahapopka” – Aha, according to Christmas (2011), translates to mean “potato,” and popka, to mean “eating place” - (Seminole: potato eating place) - is a relatively small City in the northwest section of Orange County, in the central part of Florida – approximately 20 miles north of the City of Orlando (see Appendix A).

Figure 4 Map of Florida & Apopka

Map to the left shows Apopka and its location in Orange County, and the map to the right shows Orange County and its location in the state of Florida.

Figure 5 Map of Lake Ahapopka

This photograph shows Lake Apopka, shown as Ahapopka (Seminole; The Big Potato) on the 1838 “Map of the Seat of War in Florida”. The lake is shared by both Orange and Seminole counties in Central Florida.

Today, Apopka has an estimated population of 48,382, according to a 2015 mid-year estimate from the U.S. Census Bureau. The first pioneers to settle in the Apopka area did so under the Armed Occupation Act of 1842. Historical documents show that in 1843, three families, John L. Stewart and his two sons (Jonathan and Matthew), James M. Janney, and William J. Morgan filed and received homestead permits to settle in the central Florida peninsula (Porter et al., 2009, p.9). They were the first non-native settlers to apply for and received permits to inhabited the Apopka area.

Figure 6 Capt. Jonathan C. Stewart

This photograph shows a portrait of Captain Jonathan Stewart (son of John Steward), an original settler of the Apopka area. He was an influential member around Apopka. He owned several lands and 15 slaves.

Courtesy of the Historical Society and Museum of the Apopkans. Restored on 4/3/2017 for use in this publication.

The Second Seminole War

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 - On May 28, 1930, the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which stipulated that all Native Americans residing on eastern lands will be awarded land, financial compensation, and material assistance if they agree to peacefully migrate west of the Mississippi River (Office of the Historian). A small number of tribes complied with the act and peacefully relocated west. However, most tribes refused to be displaced from their tribal lands (Office of the Historian). As a result, Congress signed the Treaty of Payne’s Landing, which compelled Native Americans to migrate west. You’ll be posting loads of engaging content, so be sure to keep your blog organized with Categories that also allow visitors to explore more of what interests them.

Figure 7 Excerpt from the Indian Removal Act of 1830

This photograph shows the 1830 Act that called for the removal of the Native Americans from any state or territory.

The Treaty of Payne’s Landing of 1832 - On May 9, 1832, a treaty was signed between the United States and the Indigenous people (Seminoles) of Florida's contemporary state, stipulating that all Native Americans relinquish to the U.S. all claims to the lands they occupied. The treaty also compelled the Native Americans to vacate within three years (U.S. Cong., 1830). Faced with the reality of inevitable eviction from Florida to the West of the Mississippi River, the Native Americans held their ground. They refused the forced emigration set forth by the United States. According to an 1836 correspondence from Andrew Jackson to James Gadsden, the United States, under the directive of President Andrew Jackson, dispatched the U.S. Army in an attempt to persuade the Native Americans to comply with the Treaty of Payne's Landing; instead, this attempt initiated a seven-year-long conflict known today as the Second Seminole War (or Florida War).

Figure 8 Excerpt from the Treaty of Payne’s Landing of 1832

This image shows an excerpt of the 1832 Treaty of Payne’s Landing. The treaty was ratified 1834 because of the Indian Removal Act passed by Congress in 1830.

The Seminoles are a collective band of Native Americans throughout Florida that engaged in conflicts with United States authorities. These conflicts are known today as the Seminole Wars. The second of these conflicts transpired from 1835 to 1842 between U.S. forces and the Seminoles over native lands. The Seminoles believed that their lands were encroached and therefore rebelled against external occupation. These conflicts are collectively known as the Second Seminole War or the Florida War. According to Porter et al. (2009), the Second Seminole War, which was exacerbated after two coordinated Seminole attacks against separate U.S. Army regiments, was carried out. Coacoochee was a prominent figure, among other Seminole Chiefs, that led the resistance against U.S. forces. Coacoochee was a local of the Apopka area, born approximately 1808 on the adjacent side of the Ahapopka Lake in central Florida and lived on the lake shores at the beginning of the Second Seminole War (The University of Michigan, 1956).

Figure 9 Chief Coacoochee (Wild Cat)

This image shows Coacoochee's (Wild Cat) sketch, a Seminole Chief who led approximately 200 men in the resistance against the U.S. encroachment of native land. He was one of the most feared chiefs during the war. Photograph Source: Public Domain. Recolored on March 26, 2017

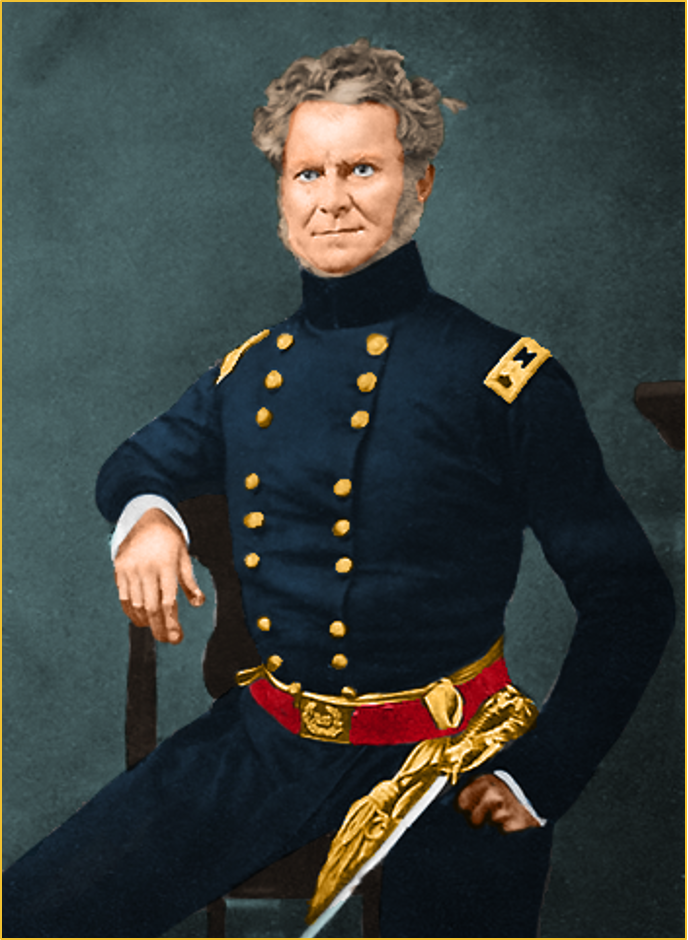

Figure 10 Colonel William Jenkins Worth

This image shows Colonel Worth's portrait, the last commander of the United States Forces in Florida that fought against the Seminoles during the Second Seminole War. He is credited for ending the war in 1842. for use in this document. Photograph Source: Public Domain. Recolored on March 26, 2017

As stated in J.T. Sprague's correspondences, a captain of the Army's 8th Infantry appointed by Colonel William J. Worth to oversee Indian affairs in the Tampa district, the area surrounding Ahapopka Lake was the motherland that gave birth to the Second Seminole War (U.S.Cong., 1846). In 1835, a brilliant Seminole chief named Coacoochee (Seminole: Wild Cat) led approximately 200 men (Native Americans and a few Blacks) on a seven-year insurgence against the Americans infringement of Seminole lands. Coacoochee was one the most notorious Seminole leaders of his time.

According to the State Library and Archives of Florida, Coacoochee was captured two times by the U.S. Army. The first time was on October 21, 1837, when Chief Coacoochee and Chief Osceola (another influential Seminole leader) were tricked by U.S. authorities under the guise of a truce and incarcerated in Fort Marion at St. Augustine, Florida. However, the first capture was short-lived. On November 29, 1837, Coacoochee and 19 other Seminole warriors (excluding Osceola) escaped and returned to the battlefield (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2013). Coacoochee then became one of the key leaders in The Battle of Okeechobee. Two months later, Coacoochee's position was elevated to the primary Seminole leader after Chief Osceola's unsubstantiated death on January 20, 1838 (Florida Memory, n.d.)

Figure 11 Fort Marion, Saint Augustine, Florida

This photograph shows Fort Marion (once named Castillo de San Marcos), where Native Indian were imprisoned during and after the Second Seminole War.

Figure 12 Courtyard of Fort Marion

This photograph shows an Interior view of Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Florida.

Figure 13 Native Indian Prisoners

This photograph shows Native Americans confined at Marion, St. Augustine, Florida.

Five years after Coacoochee's escape and the culmination of seven years of intensive fighting, the unmatched war capabilities of the U.S. Army finally overpowered the will of the Seminoles. Evident in the words of Chief Coacoochee in a conversation with Colonel William J. Worth after his surrender and imprisonment, "it is true I fought like a man, so have my warriors, but the white man was too strong for us" (Chapin, 1865, p.12).

Figure 11 Fort Marion, Saint Augustine, Florida

This photograph shows Fort Marion (once named Castillo de San Marcos), where Native Indian were imprisoned during and after the Second Seminole War.

Colonel Worth took command in the later stages of the war due to the many failed efforts of his predecessors to end the war. With the coerced help of Coacoochee, Worth was able to negotiate the surrender of many remaining Native Americans in the region. Also, ceasing hostilities and a presumed insignificant remainder of Native Americans (approximately 300) fleeing in South Florida swamps, Worth ultimately gave up the chase. Confident that the end of the fighting was imminent, he deemed the war over. On August 14, 1842, the United States government Colonel Worth to end the Second Seminole War.

Post War Homesteading

The authorization to end the Second Seminole War came ten days, August 4, 1842, after the United States passed the Armed Occupation Act of 1842. This event was significant in the emergence of the citrus industry in Florida because it directly influenced whites' immigration to the state. The government lured the early settlers in Florida to maintain control over the lands acquired from the Seminoles. The Armed Occupation Act served as an enticement to encourage people to inhabit the Peninsula of East Florida (see Figures 11 and 12). The act permitted heads of households and any single males eighteen years of age and older to inhabit the unsettled land in exchange for 160 acres of land (U.S. Cong., 1842). The stipulations were that the participants must:

Register and obtain a permit to settle.

Reside on the property for five consecutive years.

Build a home on the property within the first year.

Be at least two miles away from the military installation.

Bear arms in protection of self and the property.

This offer was an attractive proposal, and many Florida residents were able to acquire land under the Armed Occupation Act of 1842.

Figure 14 Excerpt from the Armed Occupation Act of 1842

This image shows an excerpt from the Florida Armed Occupation Act of 1842. This act was passed as an incentive to populate Florida. The Act granted 160 acres of unsettled land.

Figure 15 Armed Occupation Act Permit Application

This image shows an application for the Florida’s Armed Occupation Act permit. This act was passed as an incentive to populate Florida. This was filed by Elias Hart of Alachua County, Florida.

THE RISE OF APOPKA CITRUS INDUSTRY (1847 - 1895)

The Early Citrus Growers

Many Florida residence achieved great success in the citrus industry during its inception in the mid-1800s. Much so that in 1909 the Florida legislature designated the blossom of the orange tree (also known as the Citrus Sinensis) as the state flower (Florida Department of State) and in 2006, selected the orange as the official state fruit (see Appendix B).

Following the Second Seminole War, the warm climate and the promising agricultural prospects attracted many new settlers from different parts of the country to Florida. This marked the beginning of what was coined the “Florida Gold Rush” because new colonists flocked to the area in hopes of becoming rich from the citrus industry. According to the United States Census Bureau, in 1830, Florida recorded a resident population of 34,730. By 1890, Florida's population increased to a recorded 391,422, a relatively significant increase from 1830. During this period, the citrus industry exploded. Between 1868 and 1875, the cultivation of citrus fruits quickly became the primary income source for many Apopkans and the leader in selling exchange in the area.

By the mid-1870s, the Apopka area was beginning to take form, and practically every landowner in Apopka had started cultivating their lands and were planting citrus trees. Residents quickly realized the financial benefits of citrus farming and learned that farming on uncleared terrains was no easy feat. The early settlers found it extremely difficult and dangerous to clear their disheveled lands. This challenge was compounded by the hot Florida summer climate, which forced farmers to wait until the winter to clear their lands to avoid heat-related illnesses (Magura, 1979). In addition to oranges, some growers also raised livestock and therefore had to ensure that their cattle did not consume the citrus plants. The growers had to ensure that the animals were penned and kept away from the groves while the trees grew (Apopka Historical Society).

Figure 14 South Lake Apopka CGA Packinghouse

This image shows a photograph taken of workers at the CGA packing house in Apopka, FL.

With the expansion in citrus harvest, development resulted in the other related industries. In the late-1880s, Clay Springs Wine Company, Larsson and Company, and Piedmont Winery emerged as the new wine industry's faces - Piedmont Winery being the most successful of the three. Most of the residents of Apopka grew citrus fruits; however, others produced grapes as well. The grapes and oranges were turned into wine at a winery operated by Jonas Larson and Gust Jackson. The Larson and Jackson families opened their winery in approximately 1889, where they made wine from grapes and oranges harvested from their own citrus groves in addition to what they purchased from other growers.With the expansion in citrus harvest, development resulted in the other related industries. In the late-1880s, Clay Springs Wine Company, Larsson and Company, and Piedmont Winery emerged as the new wine industry's faces - Piedmont Winery being the most successful of the three. Most of the residents of Apopka grew citrus fruits; however, others produced grapes as well. The grapes and oranges were turned into wine at a winery operated by Jonas Larson and Gust Jackson. The Larson and Jackson families opened their winery in approximately 1889, where they made wine from grapes and oranges harvested from their own citrus groves in addition to what they purchased from other growers.

Figure 13 Larson & Jackson Wine Label

Taken on February 7, 2017, this photograph shows an 1895 honorable mention award given to Larson and Company - displayed at the Apopka Historical Society and Museum of Apopkans.

Figure 14 Larson & Jackson Wine Label

Taken on February 7, 2017, this photograph shows a label used by Larson and Jackson Winery on their wines - displayed at the Apopka Historical Society and Museum of Apopkans.

The Piedmont Winery and Larson & Company won awards for their wines at the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia. Piedmont winery was awarded a medal for the excellent quality of its orange Wine (Shofner, 1982), and Larson and Company of Apopka received an Honorable Mentioned Award with a Bronze medal for their orange and grape wine. As can be seen from Table 1, in 1889, Piedmont winery sold 3,360 gallons of their wine made for $8,572.

THE FALL OF APOPKA CITRUS INDUSTRY

Naturally, since citrus fruit had been the vital commodity that influenced Apopka exports, it can be argued that as the citrus industry went (rise or fall), so did the economy of the city. It is conceivable that Apopka had an almost exclusive reliance upon the citrus industry. This dependency on one commodity can be a detriment to long-term stability and longevity. As shall be seen below, the harsh ice freezes of 1894 and 1895 reinforced the assumption mentioned above.

The Citrus boom continued from the mid-1880s until the great freezes of 1894 and 1895. The freezes have been the seminal event in the modern history of the citrus industry. The impacts of the 1894 and 1895 freezes – (impact freezes) – for the Apopka citrus growers have been profound, for they have shaped the contours of Florida's History and Apopka's citrus Industry. Without first having insight into the impact of 1894 and 1895, no thoughtful examination of the citrus industry's current state would be complete.

The First Assault (1894 - 1895)

In the Theater of War, generally, the first military assault serves two critical strategic goals. First, to soften the target, and second, a showcase of military might. The first impact freeze that devastated the state of Florida accomplished precisely that. On December 29, 1894, nature launched an unprecedented assault on the citrus groves throughout the state, inflicting immense damage to the crops. The blitz began without warning and was an exhibition of might never before seen by the growers. The impact of the freeze was almost immediately felt. The chilling temperatures and ice formation caused the fruits to separate from the stems and fall to the ground. This effect is most likely a result of the physical damage experienced by the plants. According to Snyder & Melo-Abreu (2005), most tropical fruits and vegetables experience physiological damage when subjected to temperatures approximately 13° Celsius and below, hence temperatures above freezing. Lacking today's technological breakthroughs, the citrus growers of the late 1800s had no tools or techniques to forecast inclement weather and freezing temperatures. The growers were also ill-equipped to devise and implement preventive measures.

Figure 15 The Great Freeze of 1894-1895

This photograph shows destroyed citrus crop on the ground after a Florida orange freeze. Retrieved from Florida Memories.

By the time the growers were able to fully realize the enormity of the freeze event, a second wave of chills and freezes were well on their way. On February 7, 1895, 41 days after the first freeze, nature launched a second wave of chilling and freezing temperatures, compounding the damages previously inflicted and ultimately changing the dynamic of the citrus industry.

The impact freezes of 1894 and 1895 was an assault with crippling effects on Apopka's economy, as many of the city's early pioneers invested heavily in the citrus industry. Given the freezes' consecutive nature, the results were shattering, affecting the lives of the residence and the citrus industry as a whole. In Apopka, no "normal" short-term response to the tragedy could have produced a remedy that would have prepared growers for the years to come. Immediately following the freeze events, the most tangible economic effects were that the freeze destroyed many crops and trees, production diminished, residence abandoned homes and groves, and businesses were forced to shut down. Essentially, the impact freezes severely impaired the mechanism responsible for generating capital in the region: The freeze virtually ruined the Apopka economy. The citrus industry was but a shadow of its former self. It showed no signs of the economic prosperity that it was once known for. Between February 1895 and December 1896, Apopka shipped a record low number of fruits out of Apopka. According to (see appendix E), only seven boxes of fruits were shipped during that period, significantly reducing what was sent in the previous years. As a result, many Apopkans abandoned their homes, what was left of their orange groves, and returned north or relocated to other similar climates to such as California, to seek better opportunities (Attaway, 1997).

Businesses were not spared. In 1897, Piedmont Company, the strongest of the three wineries, only produced 400 gallons of wine (see table 1). The wine production decreased by 88% within eight years, from its 1889 count of 3,360 sold. It was because of the two monumental impact freezes of 1894 and 1895. Clay Springs Wine Company and Larson and Company both fell victim to the freezes, and they were forced to close their doors – leaving Piedmont Winery in business until it too was forced to close its doors in about 1900 (Christmas 2011).

The Aftermath

There was a renewed energy and growth of the Citrus economy from 1897–1989. Those who were able to endure the 1894 and 1895 freezes' vigor and decided to replant their groves were again prosperous. By the turn of the century, one company emerged to be the citrus industry's face in central Florida - Plymouth Citrus Growers Association, a fruit packaging plant founded in 1909 by citrus growers and whose members were made up of growers from around the area. The company was one of the largest and most stable employers in the region (Christmas. 2011). Plymouth Citrus Growers Association became prevalent and took the place of The Florida Fruit Exchange. This fruit packaging plant closed its doors following the big freezes of 1894 and 1895 and their members (Christmas. 2011).

Figure 16 Photo of the Plymouth Citrus Growers Association

Plymouth was also heavily involved in frozen orange juice products. Plymouth worked collaboratively with a small research company, known at the time as the National Research Company, to create the process for making concentrated orange juice. The National Research Company leased a small space in Apopka, FL, from Plymouth Citrus Growers Association, where they squeezed and canned concentrated orange juice for long-term use. Today, this small research company is known as Minute Maid (Jackson, 1988).

Figure 16 Minute Maid Factory - Apopka, FL

Photographs taken in 1963 by Charles Barro of the workers at the Minute Maid fruit processing plants in Apopka, FL.

By the mid-1900s, the newly reorganized citrus growers of the Plymouth Citrus Growers Association were still experiencing a state of stability unlike what was experienced after the freezes of the 1890s. The citrus industry survived the freezes of February 2, 1917, the freeze of December 12, 1934, the record-breaking temperatures (49.7 degrees Fahrenheit) of January 1940, and then again in 1957, 1962, and 1977 (Attaway, 1997).

Figure 17 Grower's Statements

Taken on February 7, 2017, this photograph shows grower's statement - displayed (in binders) at the Apopka Historical Society and Museum of Apopkans.

Despite all the success the citrus industry experienced in the 1900s, the freeze's consecutive blows on to the citrus industry finally took its toll. The collective effects of the freezes of 1981, 1983, and 1985 equated to a condition that killed over 200,000 acres of citrus plants in the central Florida area. Before any practical efforts could be made to revive the groves, a 1989 freeze punctuated the period by permanently putting the Plymouth Citrus Growers Association out of business. According to a 1983 newspaper clipping from the Apopka Historical Society, the economic impact caused by the closure of the Citrus Growers Association was $50 - $60 million per year.

SUMMARY

This paper demonstrated how the story of a century-long barrage of freezes is of incalculable importance in understanding the citrus industry's current state in Apopka, Florida. The citrus industry throughout Florida has drastically changed as production dropped due to a series of major Florida freezes. "What longstanding impact did the Major Florida Freezes have on the citrus industry of the city of Apopka?" The "impact freezes: were responsible for a lot more than changing the citrus industry course in Apopka. The freezes damaged many groves in such a way they have not recovered to their former glory and worth. It has shattered and fragmented the way of life for many Apopka, rearranged the citrus industry in Apopka, Florida, and the industry as a whole throughout the United States.

REFERENCES

Attaway, J. A. (1997). A history of Florida citrus freezes. Lake Alfred, FL: Florida Science Source.

United States. Census Bureau. (2015, July 1). Census.gov. Retrieved February 13, 2017, from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/1201700,1253000,00

Apopka Historical Society. (nod). History of Apopka. Retrieved February 12, 2017, from http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~flahs/content/history.htm

United States. Census Bureau. (2015, July 1). Census.gov. Retrieved February 13, 2017, from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/1201700,1253000,00

Chapin, J. R. (1865). The Historical Picture Gallery, Or, Scenes and Incidents in American History: A Collection of Interesting and Thrilling Narratives from the Written and Unwritten, Legendary and Traditionary, History of the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Library.

Christmas, J. R. (2011). Tales of the Big Potato. Apopka, FL: NewBookPublishing.com, a division of Reliance Media, Inc.

Florida Department of Commerce. (n.d.). Seminole Indians of Florida. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from http://www.naplesnative.com/Documents/2013/Florida%20Comments%20-%20Seminole%20Indians.pdf

Florida Department of State, Division of Historical Resources. (n.d.). State Flower. Retrieved March 26, 2017, from http://dos.myflorida.com/florida-facts/florida-state-symbols/state-flower/

Florida Memory. (n.d.). Osceola (ca. 1804-1838). Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/257494

Institute of Museum and Library Services, Florida Department of State. (2013, November 15). Tag Archives: Second Seminole War (1835-1842). Retrieved March 5, 2017, from http://www.floridamemory.com/blog/tag/second-seminole-war-1835-1842/

Jackson, J. (1988, December 21). Plymouth Juice Plant Is History Warehouse Concern Buys the Property. Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved February 24, 2017, from http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/1988-12-21/business/0090180061_1_citrus-products-processing-plant-citrus-growers

Magura, B. (1979, November 15). Florida's Juicy Past. Florida Agriculture.

Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, United States Department of State. (n.d.). Indian Treaties and the Removal Act of 1830. Retrieved March 04, 2017, from https://history.state.gov/milestones/1830-1860/indian-treaties

Porter, T. M., Fyotek, C., Antequino, S. G., Meléndez, C. C., Kremer-Wright, G., & Knowles, B. (2009). Historic Orange County: the story of Orlando and Orange County. San Antonio, TX: Historical Pub. Network.

R. (Director). (2015, March 1). Episode 38: Citrus Industry (A History of Central Florida Series) [Video file]. Retrieved February 15, 2017, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VJEJ_Tz4ZO0

Robison, J. (1998, June 28). Swedes in Piedmont Kept Tradition Alive in New Land. Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved from http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/1998-06-28/news/9806260924_1_piedmont-orange-wine-grape

Sanchez, J. (1985, June 5). Collectors Documents show art of Citrus shipping in 1800s. Orlando Sentinel, p. 16.

Shofner, J. H. (1982). History of Apopka and northwest Orange County, Florida. Tallahassee, FL: Sentry Press.

Snyder, R. L., & Melo-Abreu, J. P. (2005). Frost protection: fundamentals, practice and economics. Rome: FAO.

State Library and Archives of Florida. (n.d.). Thomas Sidney Jesup Diary - Biography of Thomas Sidney Jesup. Retrieved February 22, 2017, from https://www.floridamemory.com/collections/jesup/essay.php

The Churchman (Vol. 73). (1896). Retrieved March 4, 2017, from https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=W2AxAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.RA13-PA43

The University of Michigan. (1956). National republic. A monthly review of American history, policy, politics and public affairs. (Vol. 44-45). Ann Arbor, MI: Washington.

U.S. Cong. (1830, May 28). An Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi (pp. 411-412) [Cong. Act from 21st Cong., 1st sess.].

U.S. Cong. (1842, August 4). An Act to provide for the armed occupation and settlement of the unsettled part of the Peninsula of East Florida (pp. 502-503) [Cong. Bill from 27th Cong., 2nd sess.].

U.S.Cong. (1846). United States congressional serial set (Vol. 494) (The Senate of the United States, Author) [Cong. Doc. 494 from 27th Cong., 2nd sess.]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. G.P.O.

United States Census Bureau. (n.d.). Resident Population and Apportionment of the U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved March 29, 2017, from https://www.census.gov/dmd/www/resapport/states/florida.pdf

APPENDIXES

Appendix A - The Big Potato v.s. The Potato Eating Place

There are conflicting historical data to the correct meaning of the name Ahapopka. Some historians believe the word means “The Big Potato; others call it “The Potato Eating Place.” I believe that the Seminoles used both names. I assume that the Natives call the Lake Ahapopka “The Big Potato” and the area surrounding the lake, The Potato Eating Place.

Appendix B - The 2005 Florida Statutes | State Fruit

Appendix C - Florida’s Resident Population, 1830 - 2000

Comments